Burton Hastings

Copston Magna

Stretton Baskerville

Withybrook

Wolvey

Wolvey

– a brief history

Prehistoric

times

A

number of stone tools discovered in the Wolvey area date to the earliest

stages of Lower Palaeolithic before or at the outset of the Anglian

glaciation. Radioactive dating gives a date of about 500,000 years ago.

The landscape of the area at that time was totally different and likely to

have been in the basin of the Bytham River, which drained into the North

Sea. It was Britain’s largest river. The river’s wide banks may have

provided the route into Britain from the continent for these early

inhabitants. We do not know exactly how or where they lived as their tools

have been recovered from the debris of subsequent glaciation. There is no

evidence of activity then until after the Ice Age when the Mesolithic

hunters and fishers left some of their flint tools along the Anker

valley.

By this time

the landscape was much as we know it today with sand and gravel soils on

the higher ground of the village and heavy boulder clay to the south which

would probably have been forested at that time. Access

to Wolvey then would most likely have been along the tributaries of three important rivers

which rise in the Wolvey area. These tributaries, the Anker (leading to the Tame and the Trent),

the Little Soar (to the Soar and the

Trent) and the Withybrook stream which joins the Sowe

and eventually the

Evidence of Late Neolithic and Bronze Age activity, some four thousand years ago, is abundant on the well-drained and easily managed sand and gravel soils. In contrast little is found on the boulder clay to the south, which was probably forested at that time. A number of fields have yielded evidence of flint tools, some stray finds but others more likely to represent flint-knapping sites; it appears that the flint was brought to the area to be worked into tools for the local community. The tools include arrowheads, knives and scrapers, indicating that hunting and the preparation of animal skins took place here. A number of mounds in the area, built of turf, cover the burials of some of Wolvey’s Bronze Age inhabitants. Ring ditches and possible henge monuments also occur in the area which may have been for burial as well as ritual purposes.

Roman

times

Aerial

photography reveals that there were Iron Age and Roman farmsteads in the

area. There are also two roads which were built by the Roman army early in

the occupation. The Fosse Way, connected Exeter with Lincoln and was

probably built on an existing trackway; it formed the first Roman frontier

following the invasion in AD43. The other road is Watling Street which

connected Richborough on the Channel coast via London with Wroxeter and so

into Wales and the north. Both roads are included in the 3rd century AD

Antonine Itinerary of routes throughout the Roman Empire. Thus,

Wolvey has been strategically

placed in the national road network since Roman times.

At the intersection of the two roads, the Roman settlement of Venonis (now

High Cross) developed. It was on Watling Street that Boudicca,

queen of one of the British tribes was defeated by the Romans, probably

not far from Wolvey.

Dark

Ages

Little is

known about the area in Anglo-Saxon times. By the tenth century AD, the

Watling Street formed the boundary between the Anglo-Saxon and the Danelaw

lands. The Domesday Book of 1086 indicates

that Aethelric held land in Wolvey before the Norman conquest and also that

there were a number of other settlements in the area.

The name of Wolvey - Ulveia - is

also recorded for the first time in the Domesday Book which tells of

arable, pasture and meadow there and indicates there were 22 households

including a priest and therefore presumably a church.

The earliest part of the fabric of the present church is a 12th

century doorway. Wolvey was prosperous enough

by this time to provide a

weekly market for the area. It was

also the scene of an annual fair on St Mark's Day, a tradition which

continued into the 19th century.

There

were other settlements within the parish; one with its own chapel, known

as Little Copston, long since disappeared, while another, recorded in the

Domesday Book was Bramcote (Brancote).

They were agricultural communities, arable and pasture, with

supporting crafts like smiths and millers, and operated within the feudal

system. Much of the land

was farmed for the benefit of Combe Abbey;

one farm at Wolvey, which included a large fish pond, had been

given for the benefit of the Knights Templar in 1257 – hence the current

name of

Dissolution

of the monasteries

Such land was removed from the

religious orders following the dissolution of the monasteries in the

mid-sixteenth century. The

manorial system however continued with strips of land cultivated by

copyhold tenants in an open field system with shared grazing areas,

controlled by two Lords of the Manor, the Marow and Astley families.

This system lasted for another two hundred years until changes in

farming practice led to the enclosure awards in Wolvey of 1797.

Towards

the modern Wolvey

It is from this time a number of features associated with

modern Wolvey begin to emerge. The road pattern as we know it today was

laid out. A school was

established by the Vicar of Wolvey for poor children about 1784 and the

Baptist Chapel was built 1789. By

this time the industrial revolution was leaving its mark on rural Wolvey

both in farming and in the work of its inhabitants.

The 1841 census lists 742 people and records more people employed in framework knitting

than in farming; farm labouring brought in about nine shillings a week;

knitters could earn up to 12 shillings a week. Thus the Leicestershire

hosiery industry impacted on Wolvey although about mid-century some silk

ribbon weaving was being undertaken, most likely linked to the

By the end of the century

Wolvey's population had grown to 923 inhabitants, the majority living from

farming and its support services; there was a village smithy and a wheelwright but also a

number of traders in Wolvey: butchers, bakers, grocers, coal dealers and

other shopkeepers.

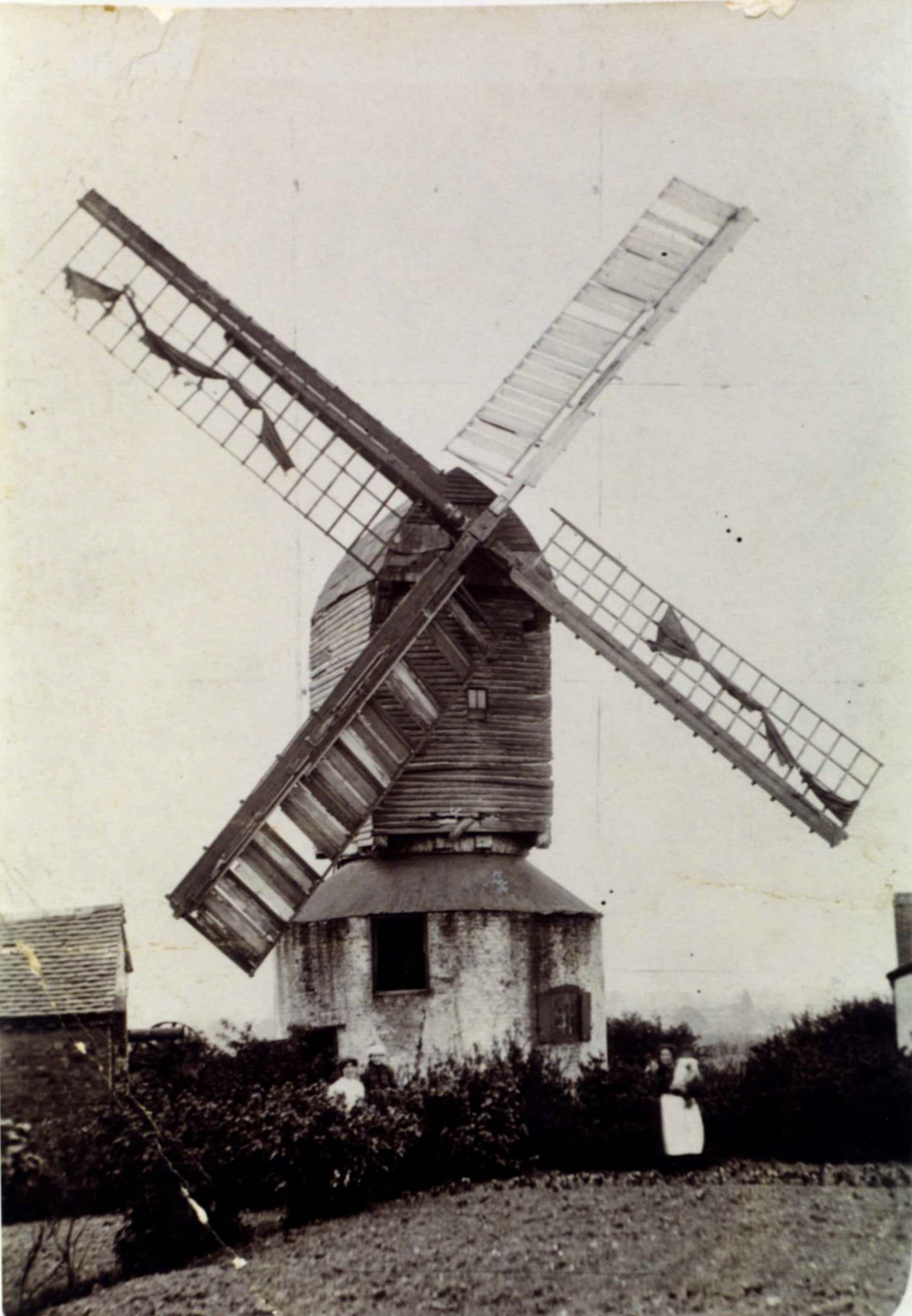

A

note on Wolvey's windmills

Wolvey has been regarded as a place with many windmills in earlier times.

Arthur Mee claimed

in his book on Warwickshire, published in 1936, that Wolvey "was a thriving town of knitters and

millers in the Middle Ages, with 27 windmills vaunting their sails" . There is, however,

no documentary or archaeological evidence to support this claim. A deed

records one windmill on the Temple Manor estate in the 16th century. The

only other firm evidence relates to a windmill, transported from Shepshed,

Leicestershire and re-erected at Wolvey on a site behind the present-day

Mill Row in 1815. This can be seen in the photograph (left). It was demolished in 1909.

Wolvey has been regarded as a place with many windmills in earlier times.

Arthur Mee claimed

in his book on Warwickshire, published in 1936, that Wolvey "was a thriving town of knitters and

millers in the Middle Ages, with 27 windmills vaunting their sails" . There is, however,

no documentary or archaeological evidence to support this claim. A deed

records one windmill on the Temple Manor estate in the 16th century. The

only other firm evidence relates to a windmill, transported from Shepshed,

Leicestershire and re-erected at Wolvey on a site behind the present-day

Mill Row in 1815. This can be seen in the photograph (left). It was demolished in 1909.

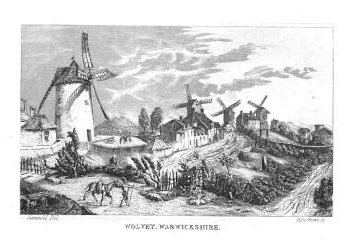

In

1854 Thomas Dugdale published an engraving in Curiosities of Great

Britain: England & Wales Delineated, (Volume 10, p. 31) purporting to show four

windmills at Wolvey. The engraving was by H. Jackson and considered to be

from a study by a local artist Sam Noll.

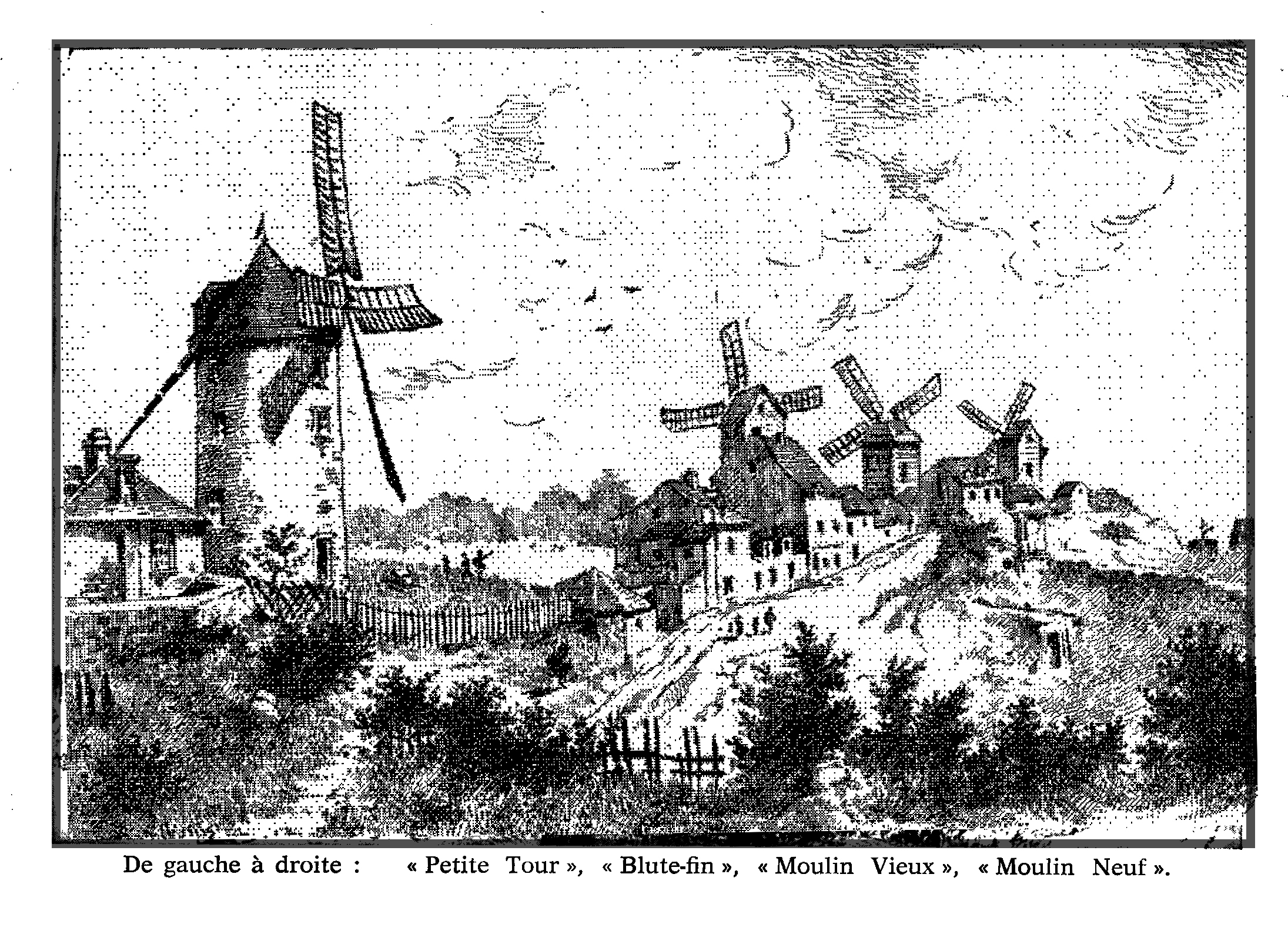

Recent research has shown this to be fraudulent and to have been taken from a French engraving of four of the windmills on Montmartre in Paris. There were thirty windmills on Montmartre and they have been the subject of many paintings by artists as well known as Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh. It was through this that the forgery was discovered.

This version of the engraving is taken from Lydia Maillard's book Les Moulins de Montmartre et leurs Meuniers (p. 99). The Blute-Fin windmill still survives as a private property. It was built in 1622.